- Accidents and Incidents

- Posts

- Monday in Mannheim

Monday in Mannheim

A collection of essays that I didn't write

This is an essay that I didn’t write about a man who woke up one morning and chose violence.

They say you shouldn’t write about the murderers, that you shouldn’t center their stories. They say that it glorifies savagery. They say that these narratives steal attention from the victims, who deserve to be remembered.

But the victims, twenty-five people struck by a fast-moving car–eleven people seriously injured, two people dead–did not choose to be attacked. They didn’t wake up that morning and make a decision. They were just there, in Mannheim on Rosenmontag, walking outside on a sunny March day.

This is an essay that I never intend to write about Fasching, Germany’s version of Mardi Gras. About a March trip to meet my mother to enjoy Mannheim’s week-long carnival festivities for the first time in years, enticed by the fortuitous coincidence that it was the same week as both of our birthdays.

Western storytelling tradition demands that we focus on active characters, on people who drive the narrative forward. The critique is predictable. “Your characters need stronger motivation. They need to make choices, not just react.” But when someone tries a Ford Fiesta at high speed through a pedestrian zone, reaction is the only authentic response. The conventional hero has no place in such an unthinkable narrative.

Sometimes story-telling traditions are wrong.

Central Mannheim is bordered by two rivers: the Rhine and the Neckar. It’s nicknamed the Quadratestadt, a reference to the 17th-century grid pattern of letters and numbers: K7 to U6 to L15 to A5 and back to K7 via C8 takes you around the city’s circumference. Atlas Obscura calls it the city where the streets have no name. This isn’t quite true: some of the streets have names, they just aren’t used for addresses. The Breite Straße runs vertically from the curve of the horseshoe through the market square and Paradeplatz to the castle. The road across, Planken, runs from the Wasserturm through Paradeplatz to the bridge across the Rhine to Ludwigsafen. Paradeplatz is at the center where the two roads cross.

My mother went to high school here and has the uncanny ability to navigate the grids without sounding like she is reading chess notations. She’d arranged for us to stay in a small hotel near the market square, in a predominantly Turkish area. Over half of central Mannheim’s population is of a migrant background. Many Turkish families settled in Mannheim as a part of guest worker programs in the 1960s and 70s, leading Mannheim to become one of the most multi-cultural cities in Germany.

Not everyone approves.

This is an essay that I abandoned about the luxury of looking away.

We walked from our hotel through the market square and along the Breite Straße towards Paradeplatz. It was the week of carnival, and we were both looking forward to visiting the street stalls that soon would fill the Planken, connecting the festivities already in place at the Wasserturm and at Paradeplatz. As we walked, my mother held up a hand, pausing our conversation to tell me to listen: sirens.

“Police,” she said. “Something has happened.”

“Maybe an accident?”

“Maybe. But why police not ambulances?”

I shrugged. “Why not both?”

We kept walking, reaching the Paradeplatz at the same time as three police cars. Two others were parked askew, pointing towards an open ambulance abandoned in the middle of the intersection.

A woman lay collapsed on the pavement, a paramedic kneeling at her side. There was something large next to her that I couldn’t make sense of. Had she fallen ill? But then, why all the police?

Across the intersection was another body, another paramedic kneeling over it. Something was very very wrong. I turned to my mother, who looked as confused as I was. “We should get out of here,” I said. “Now.”

As we turned away, people were starting to cluster and stare. I followed their gaze to the woman on the pavement, my eyes sliding over the shrouded shape lying ignored beside her.

The paramedic looked up, staring confusedly at the growing crowd. “What are you doing here? Go!” His voice was unexpectedly emotional. “If you don’t need to be here, just go. Go home, if you can! Go home!” His voice cracked on the word home. He wasn’t angry. He was scared.

A businessman barked into his mobile phone: a woman on the pavement near Paradeplatz, a dead body lying next to her. Another police car arrived. We fled the scene.

A black Ford Fiesta had turned from the Wasserturm onto the Planken, followed the tram tracks, accelerated through the shopping zone as people began to run out of the way, struck down pedestrians as he gathered speed, and rammed into a bench. A bench full of people who had made the simple decision that day to sit for a moment or two in the midday sunshine.

Taking refuge in a small Vietnamese restaurant, we heard fragmented details of what had happened. A couple nearby whispered that the car was still out there, circling the city, looking for a way in.

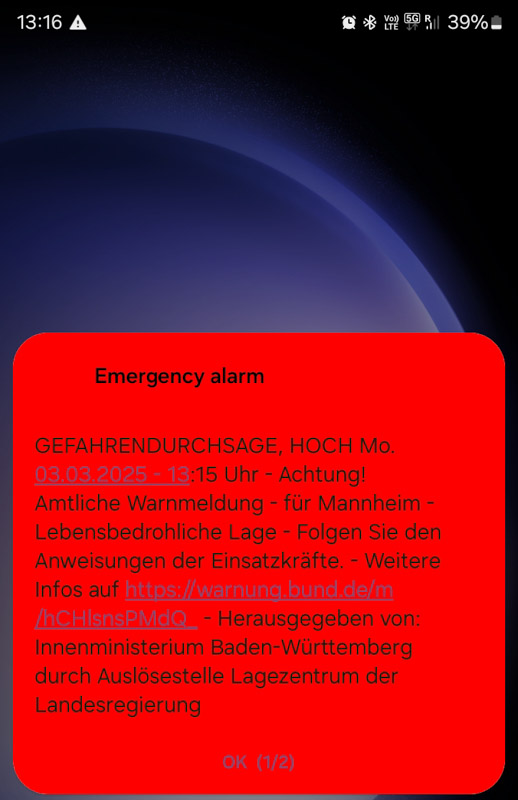

Every phone in the restaurant went off at once. My screen flashed red.

EMERGENCY BROADCAST: HIGH

Life threatening situation in Mannheim. Follow the instructions of emergency responders.

We were told to stay off the streets. It was not possible to get in or out of Mannheim city center. All of the bridges across the Rhine and the Neckar were blocked off. The city’s hospital declared a state of emergency.

People streamed past our window, one road over from the Planken, at one point breaking into a run. My mother and I agreed that sheltering in place with a bowl of pho was the most sensible option.

This is an essay that I don’t know how to write, about how trauma is used as a political statement before the blood has ever dried.

Photographs started to spread on the Internet: zoomed-in shots showing bodies face down on the sidewalk. Supporters of the right-wing fascist party called it a terrorist attack, said that Mannheim’s liberal policies and safe haven for asylum seekers were to blame, said that Mannheim got what it deserved. “This is the new Germany,” said multiple tweets all at once, showing a torn off limb in the middle of the Planken.

The oldest victim, who died on the scene, was 83-years-old. The youngest victim had just turned two.

Mannheim police updated their website: a man was in custody. He appeared to have been working alone. The city was safe again.

The soup was good. The wait staff, all immigrants, all fluent in German and English, had a haunted look around their eyes.

By mid-afternoon, police were on every corner, in cars, on foot, on horseback. White people like me looked around, took photographs. Men with darker complexions walked silently, heads down, eyes averted. At the market square, a police van parked, disgorging a dozen police in full riot gear.

We were surrounded.

It didn’t make me feel safer.

The police released another statement, this time to say that the driver of the car was a German citizen. “That doesn’t mean much,” muttered an angry man at the market square, eyeing the riot police. Another statement, this time explicit: the attacker was German, of German descent, code for white.

They say we should name the victims, not the killer, but names matter. We needed to know for sure where he was from.

His name was Alexander. Suddenly, everyone agreed that this wasn’t about a specific person or his beliefs. He was mentally disturbed, we were told. There was no political motive.

This is an essay that I don’t want to write about a man named Alexander who shared photographs of himself with heavy weapons and posing in front of tanks, who posted “Sieg Heil” on his Facebook page, who had twice previously been arrested for hate speech. But the white-skinned man choosing violence is mentally ill, as opposed to violent brown-skinned men, who are always acting politically and always representing their community.

Still, as word of the German spread, the unbearable tension began to dissipate. Although policemen were still visible on every corner, they no longer stood stiffly with weapons in hand. Their faces seemed to soften into young men and women again, just doing a job. They were still there the following morning, talking among themselves in the hushed city streets. I sat in the sunshine on a bench at Paradeplatz and watched the people pass. An old man sitting next to me smiled cautiously.

Everything was closed. All carnival events were canceled. Flowers began to collect in piles along the Planken.

This is an essay that needs a hero.

Slowly the local media caught up with events. We discovered that a taxi driver had been waiting at the taxi rank near the intersection where my mother and I had so mindlessly strolled among the victims, not yet knowing what we were seeing.

The taxi driver watched the Ford Fiesta driving fast through the people. He pulled out of the line of taxis and chased the car, shouting and honking at pedestrians to scatter, to get out of the way. The attacker-of-German-descent attempted to flee the scene, turning fast to evade his pursuer. But the grid layout of Mannheim, confusing at the best of times, became a trap. He drove straight into a dead end. The taxi driver blocked the road behind him, cutting off his escape. The attacker smashed into a wall and then abandoned the Ford Fiesta. The taxi driver jumped from his vehicle to give chase then scrambled back for his keys, realizing his taxi could become a getaway car. The attacker pulled out a gun, fired a wild shot, and then fled on foot. Disappeared into the grid as the police converged.

A handwritten note was taped to the dash of the wrecked Ford Fiesta: scribbled mathematical formulas for reaction and braking distances.

This is not an essay about Alexander but it cannot come to a close until we know his fate.

They cornered the man like a wounded animal twenty minutes later. He pointed the gun into his mouth, pulled the trigger. It was a starter pistol, firing blanks. The police arrested the German fascist and took him away. Now he is in jail, awaiting trial for two counts of murder, five counts of attempted murder, and eleven counts of grievous bodily harm.

The taxi driver was taken to hospital, where he was treated for shock. “For me, he is the hero,” said a policeman.

The taxi driver’s name was Afzal Muhammad. He was a 50-year-old immigrant from Pakistan. “I am not a hero,” he said in a press interview. “I am a Muslim. I am a Mannheimer.”

This is an essay about a man who woke up one morning just like any other morning. He didn’t make a decision to choose courage. He simply reacted.

Sometimes, that’s all the hero needs to do.