- Accidents and Incidents

- Posts

- My Relationship Status: Emotionally Entangled with Three Cities and Possibly a Llama

My Relationship Status: Emotionally Entangled with Three Cities and Possibly a Llama

I am incredibly adept at making simple travel difficult.

I have unexpectedly fallen madly and deeply in love with Buenos Aires but not quite so in love that I don’t want to check out other options. When I discover a cheap flight to Jujuy, I already know that I’m going to go. Jujuy is a province in the northwest, bordering Bolivia and Chile. The capital, San Salvador de Jujuy, sits at the foothills of the Andes. Google informs me that if I want to go hiking, then I should travel north from San Salvador to a town called Tilcara, known for its Andean festival and access to trails like Garganta del Diablo. My brain floods with visions of hiking in the Andes. I’ll drink some wine, I’ll pet a llama, maybe I’ll even do some writing.

But then I can’t book the flight: the airline tells me both that they are happy with all cards from all over the world and also that my payment card is not valid. I try three cards. None of them are valid. I can’t get past the customer services bot that tells me that I need to check if I entered my card details correctly.

There’s a third-party aggregator that looks like it scraped the flight off of Google but actually allows me to pay for the flight. Just one catch: no luggage. Not even a carry on bag, personal item only, must be tiny. They suggest that I buy extras directly from the airline that cannot manage a card transaction.

Fine. I don’t need luggage.

I strip my belongings down to the essentials. There’s a storage company that operates on some sort of decentralized custody for personal belongings. You book online, get the address of a location somewhere in your chosen neighbourhood, and give them all of your earthly possessions.

My assigned drop point is a phone shop in San Telmo, crammed with AI-art cases and knockoff chargers. I give them my number and hand them my suitcase. All I can do is trust that the shop is still here when I return.

I take the bus to the airport wearing three layers of clothing, a spare set of underwear shoved into my handbag. This was how I discovered that there are multiple number 8 buses but only one of them goes to the airport. Also, that Google Maps lies and tells you to get off three stops before the actual airport bus stop and then teleport into the terminal.

I have two phones, a Kindle, a tablet, a one-pound back-up battery and and new keyboard and a tangle of cables tucked into my hoodie pockets, looking like one of those street vendors who open up their coat and show you a wide range of goods.

At the airport, I unpack everything to pass through security. I need three trays. After I pack myself back up, a man with a wand points out that I have a cable trailing behind me.

At the gate, the Argentines start forming a queue an hour before boarding, pure social contract magic. I do try to fit in with local customs but in this instance, I stay seated like a savage until I see our plane pull up to the gate and dump its last cargo of tourists and gauchos.

Ground crew come over and split our queue into two, based on group. Group 1 is to the left, all others to the right. I smugly move to the left, eager to get on board. They split the right-hand queue again, group 3 and greater moving further right. After half an hour, the aircraft has had a cursory clean and they are ready to start boarding. This is when I realised that they are boarding right to left and Group 1 is last. I feel sad, having believed I was special, to be one of the last people on the plane, finally boarding then minutes after our expected departure.

I squish into the middle seat and try to keep my hoodie spilling over the sides, redistributing items until I finally get the seatbelt over my middle. I do not exhale for the entire two hour flight.

Jujuy airport is not in San Salvador; however, the bus to Tilcara, my chosen destination, is. I find a friendly man who tells me to purchase a shuttle ticket to the bus station. Proud that I’ve not had to take a taxi, the general recommendation for tourists, I proudly wait outside in the rain, all three layers getting damper and damper, until the shuttle bus is full and we are ready to go.

The bus station is impossibly clean and bright. A woman at an information booth appears improbably happy to see me, checks the time and tells me which bus company has a bus leaving next which will stop at Ticara. The woman at the bus company is less happy to see me but, after determining that I am somewhat stupid, writes helpful notes on the ticket: bus will arrive in 40 minutes, somewhere between bay 08 and 13, it will say Humahuaca on the front and Evelia on the side.

I wedge myself into my bus seat, attempting to take off my hoodie in a way that does not tip all of my electronics on the floor. And then we drive. The windows fog up and all I can see outside is black rain. I am desperate not to fall asleep and end up in some abandoned village full of abandoned corn husks and dessicated llamas.

It’s past eleven when the bus pulls into Tilcara. A cracked parking lot. A couple of guys loitering with intent. I check my phone: a 25-minute walk to the hostel, which I had glibly told the hostel would be easy as I have no bags.

Damp, tired, and carrying an army of electronic devices, I have regrets.

The air is thin and every road heads uphill. I can’t find any street signs. The paved road quickly deteriorates into a dirt track. Shop shutters rattle closed as I walk past. When I manage to make eye contact with anyone, I get a dead stare. Every time I check my phone map, it tells me that I’ve gone the wrong way. Again.

I should have stayed in Buenos Aires, I think. I loved every millimeter of Buenos Aires. People mostly smiled at me, said hello. There were coffee shops and restaurants and street lights. Here, there’s just dirt and altitude.

Defiantly, I mutter buenas noches under my breath at the next person coming towards me. She nods, replies. Shit. Am I supposed to be greeting people?

Two turns from my hostel, the road dips downhill. Somewhere along the way, I climbed up a hill I didn’t need to. I curse the Andean gods and keep walking.

Finally, I find the right corner shortly before midnight and punch in the night code. It’s not really a hostel; there are multiple double rooms, en suite, and mine is as good as any good hotel. I message the hostel contact to say that I’ve arrived. She sends me a stack of emojis and asks if I need a phone number to order some takeaway? No, I do not wish to tackle any more complicated things today. I sleep like the dead.

And then, morning. It’s like someone rewired Tilcara overnight. It’s beautiful. Still dusty and crumbling, yes, but also golden in the morning light with misty black and red mountains creating a backdrop that looks straight off of a motivational poster. I discover that street signs do exist, just not where you’d expect, hand painted onto walls and fences at random heights as you walk down the road.

Tilcara is unexpectedly full of restaurants, each with chalk boards scrawled with lists of amazing-sounding meals in pastel colours. I start reading them, searching in advance for my evening meal, and then pause, not quite emotionally ready to consider Llama al Malbec for dinner.

Maybe tomorrow.

I buy a bottle of water and then explore the stalls at Plaza Alvarez Prado, the main square of Tilcara. It spans a city block, with vendors set up along all four sides, sitting bored, staring in the distance. There is no one shopping; everyone looks local except for me and a backpacking couple. I walk along the stalls, making a point of showing extreme interest. I can’t really carry any souvenirs home with me, but truthfully, I could use something to carry my water in, as my trusted hoodie is still drying out in my hostel room. I pick up a brightly coloured shoulder bag, trying not to feel like every-other-tourist-to-the-Andes-ever.

The locals have stern faces carved from stone until I remember to whisper buen día in their general direction, at which point they smile and greet me. I try it louder. Everyone seems happy to see me. Some even ask que tál?, how are you?, and actually expect an answer.

I respond with a slump and a wheeze, universal code for every road in this town is uphill and I am dying. I am met with laughter, sympathy and one invitation to a cold beer (I should have said yes).

On the edge of town is an old iron bridge, Puente de Tilcara. It has 434 reviews and a star rating of 4.6. I have become obsessed with the people who review functional places as if the rating matters, as if some bridge-busybody might read the Google reviews and exclaim, “Why have we not got five stars?! We need to improve our bridginess!”

I check the four-star ratings to find out what was found wanting. One person left four thumbs up and a smiley. Another posted 15 photographs of the bridge writing:

I arrived in Tilcara with low expectations, but I remembered “When the earthquake passes,” and headed here.

It’s great to have seen it.

The bridge clearly deserves five stars. I am struggling to think of something to say about it that would justify my rating. I cross the bridge, deep in thought, and then write.

Five stars for being a perfectly functional bridge. Thank you very much to the man in the grey Fiat who waited for me to get clear before driving across.

Reservation recommended: No.

On the other side, I see a sign pointing to a trail. Google tells me that this is a hill, called Cerro de la Cruz, and although the peak of the hill is 2,600 meters above sea level, about 8,500 feet, I am already at 8,000 feet ish and it s an easy 20-minute climb.

No, I don’t know why I keep believing Google either.

An hour later, I’m at the top, glowing with perspiration and trying not to think about whether I’ll be able to walk tomorrow.

But it’s worth it. Looking down from the wooden painted cross, I have a view of Tilcara, in a valley built on a slope, shadowed by impossibly tall mountains. Behind me the landscape goes on for ever, and in the distance, impossibly, rain clouds below me. All around me loom even more majestic brown and red mountains, and I finally understand why they called this one that I am on a hill.

I swear loudly. I am in a committed relationship with Paldiski, already half in love with Buenos Aires, and now I’m crushing on some Andean city that I’d never even heard of before last week. Maybe it’s a phase I’m going through, maybe I’m just falling in love with everywhere.

I stay on the top of Cerro de la Cruz for an hour, watching the clouds drift past and the mist pile up around the mountain peaks and the cars driving to and from Tilcara.

By the time I make it back down to Tilcara, my town has transformed again. It is now full of people, tourists wandering up and down the streets, looking into the gift shops and peering at menus. The plaza is now a bustling center of tourist trade. Where have they all come from? They do not look to me like the type of people who would spend an hour and a half on a bus wearing three layers of clothes.

Around the corner, I see my answer. A gleaming white two-level air-conditioned luxury coach. There are, I discover, day trips to Tilcara from Salta and San Salvador, where people travel in comfort to be dropped on various Andean cities to purchase multi-coloured bags and llama braised in malbec. Their experience is not my experience, of course. They have never walked up through Tilcara at midnight in the rain, wondering what the fuck they were doing there.

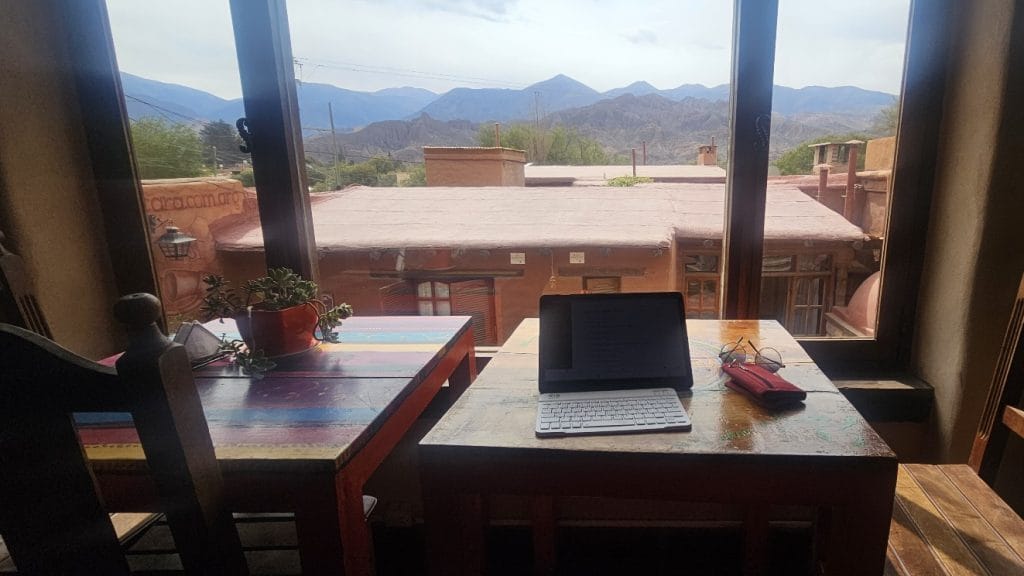

Once again feeling smug about my travel prowess, I head back to my hostel and begin to write.