- Accidents and Incidents

- Posts

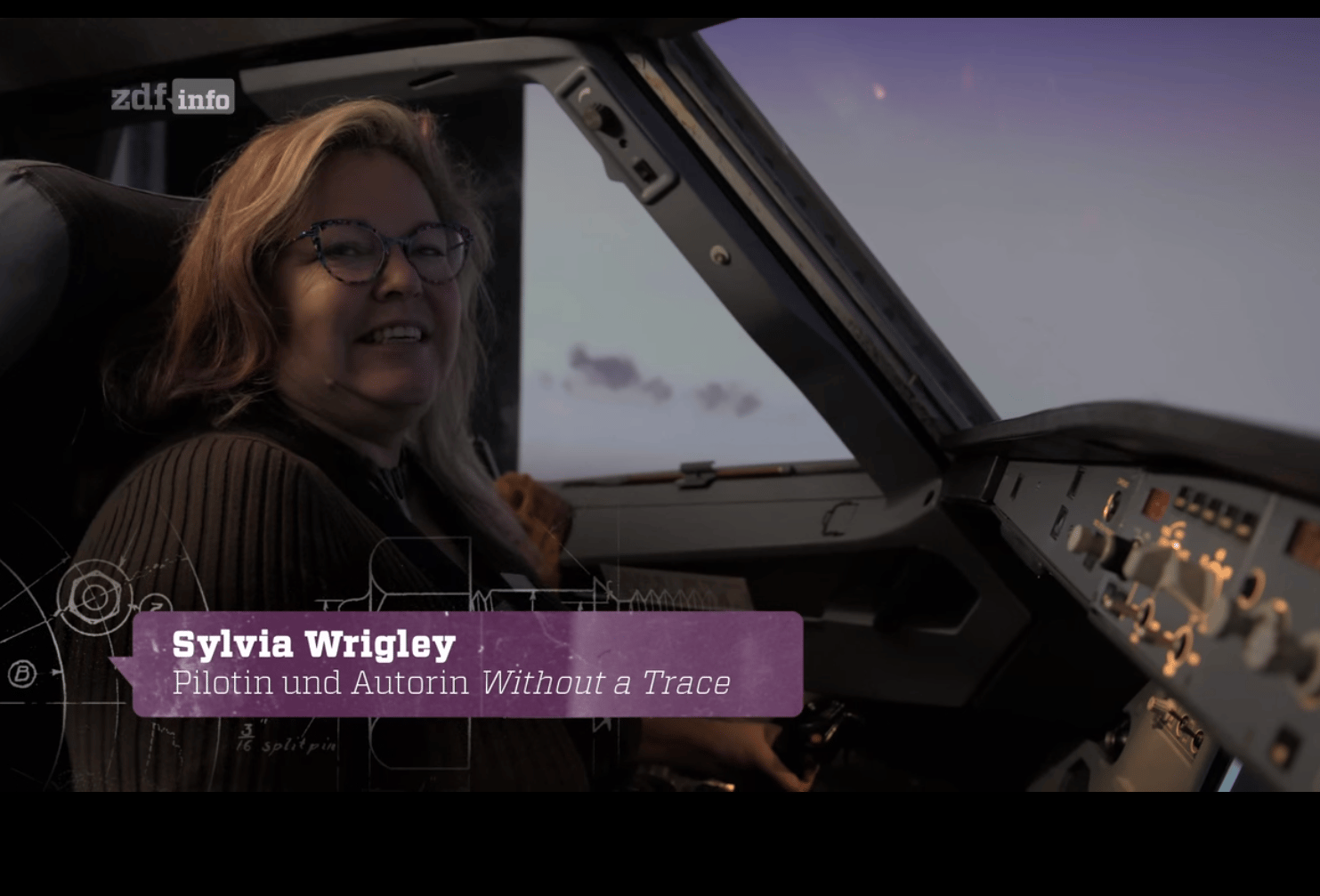

- They Let Me Fly the Plane

They Let Me Fly the Plane

I successfully crashed an A320. Seven times. Six of them on purpose.

I was asked to take part in a documentary about Flight 19, the mystery which is credited with starting the myth of the Bermuda Triangle. In December 1945, a squadron of five torpedo bombers, Grumman TBM Avengers, disappeared off the coast of Florida during a routine training exercise.

I've done work like this before. Usually it's done in a studio. I sit in a chair with an interesting backdrop behind me and answer questions about the events leading up to the disappearance and explain some of the aviation aspects - for example, how to navigate using dead reckoning. In this case, the production people told me they would be interviewing me at a flight training school. They were going to use the simulator there to recreate the flight route and weather conditions of Flight 19. I could then answer questions that came up as a part of the simulation.

"Cool idea, I said. "Will I get to get into the simulator?"

"Sure", said the director.

Maybe if I was lucky, I thought, they'd put me in the right (co-pilot) seat and interview me there. That would be pretty neat, I thought. I would like that.

They didn't seem to be aware that I had any pilot experience and, in retrospect, I think they were disappointed to discover that I had. You know how they do TV shows with a young and bouncy celebrity who giggles a lot while she tries to do something she clearly can’t and then talks about how it felt with wide eyes? That was, it seems, what they were hoping for.

How they ended up deciding I was the right person for this is still a mystery.

I wrote about Flight 19 in Without a Trace and having spoken to their researcher, I felt pretty confident that I could answer any questions they threw at me about what happened that day. Most of my preparation involved trying to find an outfit that was camera safe (no white, no black, no patterns, etc.) and that made me look professional and yet easy to approach while also being comfortable enough to wear all day.

The morning of the filming, I oversleep, with just enough time to tug on the green outfit with the gold scarf, throwing two extra outfits and a full set of make-up into my bag before rushing out for my Uber. I do my make-up in the back seat and hope that I might get a moment to touch up while they film the simulation.

There's no traffic and I arrive ten minutes early to find the building dark and the parking lot deserted. The director replies to my message telling me that I was early and he was about to stop for coffee. Did I want one?

It's half an hour before sunrise and just above freezing. I resist the urge to reply with selfies of myself shivering in the dark and ask for a cappuccino. He sends a thumbs up in response.

A van pulls up twenty minutes later and I gratefully accept the offer to climb on board and thaw before even asking if the three men inside are the people I am there to meet.

The director hands me a coffee and explains that while we are waiting for the flight centre staff to arrive, he wants to film me walking through the parking lot to the front door of the building. The sound engineer remains in the van while the director and the camera man attempt to steer me through what seems like a relatively simple shot.

I walk towards them.

"Don't look at us. Look straight ahead."

"You are straight ahead."

"Look past us. Don't turn in so abruptly. Look at the doorway before you turn, maybe with a flash of recognition as you see the sign. Do it again."

I'm an aviation geek, not an actress, I mutter under my breath as I approach the locked door of the building over and over again.

Finally, the training centre supervisor appears and the door opens for real. It was now that I discover that they want me in the left seat of the simulator, so that I can fly an Airbus A320 recreation of Flight 19's route in 1945. The A320 is playing the part of the Grumman TBM Avenger: a torpedo bomber with a single engine and a three-bladed propeller that is about 1/10th of the size and one millionth of the technology of the Airbus.

The director keeps calling it the experiment and I have no idea what he is talking about. But hell, it's a chance to fly an A320, I'm not going to say no.

There's four seats in the cockpit. I take the left seat and try to work out where the controls are. The training centre supervisor sits behind me and attempts to quickly fill me in on the controls. The camera man sets up in the first-officer's seat and the director behind him, except he's almost in my lap, reaching past me to set up a GoPro to catch my facial expressions.

"Not on the windscreen," shouts the supervisor. "It's not fastened to anything." They finally compromise on a spot on the dash. I'm still trying to work out where the lever for the flaps is.

The dials and switches light up and the black windscreen in front of me turns into blue sky and a cityscape. We're sitting on a runway.

"Fort Lauderdale," says the supervisor. "Steer with your rudders. Use full power and rotate at 140 knots."

It's happened so fast, I don't know what to say, so I comply, pushing the thrust levers forward and veering back and forth on the runway while the director fires questions at me. We lift off but I have no idea how much pressure to use on the side-stick; I am pitching the airliner up and down like a dolphin wildly as I try to answer. The camera man looks slightly green but valiantly keeps filming, asking me to look towards him because my hair is covering my face. The supervisor points out that I still need to retract the gears; we are flying with our wheels down and flaps still set for take off.

"Look at me," says the director. "Talk about how easy it is to fly."

I'm too busy to tell him to fuck off.

The lever for the flaps doesn't move and the supervisor shows me to pull the knob towards me before pushing it, a safety mechanism to ensure that it doesn't get knocked out of position. I reduce the power back and check again. Finally the aircraft is configured. We're climbing safely away from Fort Lauderdale. My dolphin-like oscillations have reduced to minor adjustments using the artificial horizon. I've not quite got it yet but I'm approaching something close to stable. I take a deep breath.

The director repeats his question.

"I'm hand-flying here." My voice is even and calm. "This is not easy."

"But you have GPS," he says. "Surely the plane just flies itself."

There's so much wrong with this statement that I don't know where to start.

The supervisor reloads the scenario and I take off again. "Look," I tell the director. "I can fly wings level OR I can keep my altitude OR I can talk. I can't do all three." Actually, I don't appear to be able to do any of the three. My climb remains erratic and I am already 40° off my heading of due east.

On the third attempt, I manage to make it to our cruising altitude while explaining what I am doing and where we are flying. It's not good enough. The director tells me that I sound too professional and am using too much jargon. "Don't explain things. Talk about what you are feeling. And look over here, so we can see your face."

"STALL STALL STALL" says the Airbus.

"Let's move on," says the director. "Where's the compass?"

The five torpedo bombers that made up Flight 19 were on a standard navigational exercise, a large triangle flying east from Fort Lauderdale for about 100 nautical miles before turning north to overfly Grand Bahama island and then south-west back to Fort Lauderdale. One aircraft would take the lead and navigate them to a set point and then turn while the instructor flew behind them and graded them on their performance.

On that day, the instructor believed that the lead aircraft had got it wrong and so he took the lead to try to get them back on track. As the weather worsened, he admitted that he wasn't sure where they were and told another instructor that he believed both of his compasses were malfunctioning.

It doesn't actually matter in my case; I was off course within seconds of us taking off from Fort Lauderdale. My oscillations have reduced to that of a sleepy caterpillar. There's no chance of my following the navigational exercise of Flight 19 even without having to deal with a bubble-faced aviation compass with the needle bouncing in time to my over-corrections.

I'm pretty sure that he's about to ask for the compass to be turned off, which is only mildly worse than saying it's easy to fly with GPS. Truth is, I'm not using either for navigation anyway, I'm just trying to keep flying.

The director pokes the supervisor. "Hey. Where's the compass?"

The supervisor leans forward to pulls down a small hatch where the compass would normally be. "There isn't one," he says. "Because we don't move. But this is where it would be."

I instinctively glance at my heading; I'm already off course again. We're somewhere over the Atlantic. Dark waves stretch out to the horizon. I have no idea where the Bahamas are.

"Couldn't you get one?" The director smiles hopefully. "We need it for the experiment."

The supervisor looks at him. "No. And if we could, it wouldn't work anyway." He says the next sentence very slowly. "Because we are not actually moving."

"OK, OK," says the director, although I'm pretty sure he still has no idea how a compass works. "Turn off the GPS."

I roll my eyes. The camera man chooses that moment to zoom in on my face.

We're already hopelessly lost. But the trainer understands better than I do how to deliver and he kills my display completely, taking every bit of data away from me other than what I can see outside the window. The aircraft pitches violently as the clouds gather.

I don't have a hope.

I turn to the camera and say "OK, now we are crashing but not because of the scenario but because I've lost control of the plane."

"Don't look at the camera," says the camera man.

"Tell us how it feels," says the director.

Behind the camera man is the heads-up display for the co-pilot, still working. I use the airspeed and artificial horizon from that display to get back into some semblance of flying while trying to describe how I feel without using any swear words.

The director waves his hand to show where I should be looking. I tell his hand that that I have 150 hours flight time and the men doing the navigational exercise only had 60 so yes, they probably flew better than me but they weren't that experienced and flying under these conditions would have been very difficult.

I've lost the plot, of course. This is nothing like what they experienced. They never lost the primary displays, they knew their pitch and their speed and their compass heading. And they wouldn't have known how to fly the Airbus A320 any more than I do. If I had half a second to think it through, I might have said that. Instead I'm wondering if I can ask him to wipe that line about my flight hours because I'm doing so badly, I don't really want anyone watching this to know that I have any pilot experience.

The supervisor speaks up, whether for my benefit or the director's, I don't know. "You've only flown 150 hours and in small planes and you are managing this complex aircraft? Respect!"

I'm not sure "managing" is the right word. We have not yet crashed, mainly because he resets the scenario every time it starts to look dire.

The director and the camera man take a quick break and try to secretly whisper to the supervisor (who is right behind me) that they want him to adjust the parameters so that I am surprised by running out of fuel. I pretend not to hear. The supervisor reloads the scenario and the Airbus politely lets me know that I'm low of fuel with a line of orange text on my flight display.

"Is that it?" The director frowns. "There's no big flashing red light or anything?"

I've already descended to avoid the storm clouds that they have created for me so as the fuel runs out, I drift towards the waves, which look surprisingly calm for a winter storm in the Atlantic. The screen goes black.

"That's it?" The director looks heartbroken. He'd hoped for a flaming crash into the sea or at least a broken windscreen or something. I almost feel sorry for him until he decides that what he needs is a better reaction from me.

"Do it again! I want to see your panic, Sylvia. I want you to make me feel your terror."

The trainer reloads us into mid-air and we try again. And again. I start to try for a successful ditching at sea before I notice that the "crash" actually happens 50 feet above the waves, before I've actually touched down.

The camera man motions at me to pull my hair out of my face. "Can't you push some buttons or something?" I turn off the master caution light. He seems happy with this.

"But how do you feel?" asks the director. "Isn't it horrible to know you are going to crash?"

It isn't but I try a small "eep" the next time the screen goes black.

"That'll do," he says. "Let's do the entire flight from the start."

The supervisor resets me to on the runway at Fort Lauderdale and then gets distracted by something on his phone. The camera man wants to focus on my hands so I show him what I'm going to do after we are safely climbing away from the runway: "I'll lift this lever to raise the wheels, then I'll raise this one to retract the flaps and then I'll pull the power back." And then I'll turn on auto-throttle and autopilot as I've worked out how to do that now... but I don't tell him that. He nods, ready.

I apply full power; we need 140 knots to lift off. As we start rumbling down the runway, I'm proud of myself for keeping the plane right in the middle of the runway without veering or over-correcting.

Apparently, this isn't exciting to anyone else. "Go on, raise the wheels," the camera man tells me, his camera pointed at the centre console where the controls are.

"I can't! We're still on the ground." We are still accelerating: 80 knots, 90...

He refocuses the camera and points at the lever. "Yes but can you do that now? Just lift it."

100 knots. No way will this aircraft take off. "I can't, we aren't going fast enough."

He sighs. I'm being difficult again.

"Sylvia, it's just a computer," says the director. "Just pull it up."

I reach for the lever.

The supervisor suddenly looks up from his phone and lurches forward to pull my hand away. "What are you doing? We're still on the ground!" He shakes his head. "It won't let you raise the gear."

"Thank god for that." But I'm pretty sure he thinks I'm the one who wanted to raise the wheels while we were still on them.

I do it again, the camera man clearly miffed at the 15 seconds it takes me to get to 140 knots and off the ground. To make things worse, this time I extend the flaps fully instead of retracting them, causing the trainer to leap forward from the back seat and retract them for me. I'm tired and I'm grumpy and I'm starting to make stupid mistakes.

“We’re almost done,” promises the camera man. "Pull your hair out of your face."

The director asks me how I feel while the camera zooms on my face. I’m still clearly not emotional enough and his questions get more and more leading. “Can you understand how the instructor for Flight 19 must have felt? What do you think it must have been like for all those pilots in those final moments? What do you think now of your theory that the instructor was wrong when he thought he was over the Florida Keys?"

It's not really my theory and I fail to see how deliberately crashing an A320 is supposed to shed light on the mystery.

“It’s an experiment,” says the director. “Did you feel frightened even though it was only a simulation?”

Eventually he accepts that I'm not going to burst into tears on camera and announces that we are finished.

As I come down the stairs from the simulator, I see that the sound engineer is setting up someone new; an older man. He has that uncomfortable look of someone who is in their best clothes, a black and white patterned shirt and black pleated trousers held up with belt drawn to the tightest hole.

The sound engineer wires him up while the director tries to convince the flight centre supervisor that the NO PHOTOGRAPHY signs in the room full of simulators don't apply to him and he wants to show off all the equipment the flight centre has; an argument which he loses.

Everyone seems to be grumbling and annoyed. The supervisor offers to make me a coffee and I accept gratefully, glad that I'm not being treated as part of the problem. As he hands it to me, the director calls my name. "We need you! Come on. We're running late."

The new arrival, it turns out, is the only flight instructor they could find on short notice who is willing to appear on film. His job, they tell him, is to brief me on how to fly the Airbus A320. No one tells him that I've already flown it.

He looks incredulous. "A briefing takes about two hours."

The director takes a deep breath, struggling to understand why everyone is making this so difficult. "Well, just do a super fast briefing, just the basics."

A shocked look from the instructor. "That would be unprofessional!"

The director does not appear to be happy with the instructor showing him how he is feeling. “That’s how we do it on television,” he explains patiently. “Things that take hours in real life happen in about 10 seconds.”

They eventually agree to film a montage of him talking to me and pointing at things with a comment that I was getting a full briefing.

This means that my inability to fly the A320 will be preceded with the statement that a very experienced flight instructor spent two hours explaining what I needed to do. Great. I swallow my pride and get back into the simulator, this time with the camera man behind us and instructor in the right seat, poking at an iPad which he will use to control the simulator.

He starts by showing me the primary instruments. "You know these," he says. "I know it looks overwhelming but the principals of flight are the same as in a single engine plane."

The camera man interrupts him. "You need to look at her. Can you two lean towards each other? All I'm getting is the back of your heads."

The instructor rolls his eyes and we lean towards each other. He nods seriously and I nod back and that's the briefing done.

He reaches over to put the iPad into its holder and the director breaks in. "Can you just keep holding it? It's a good visual."

"That's unsafe," says the instructor.

"And make it brighter. Put the route onto it or something."

The instructor taps at the iPad, setting me up at Fort Lauderdale again and then steps through what I need to do to prepare for departure.

"Don't help her," says the director. "Just let her get on with it."

The instructor blinks slowly and leans back, clearly wishing he were anywhere but here.

Power on, 140 knots, rotate.

I reach over to retract the gear and the instructor slaps my hand away. "My job," he says.

I start to explain that I was flying alone, before, and that this should tie in with the other footage and besides, I've never flown with another crew member before. I manage to get about two words out before the Airbus interrupts me.

"STALL STALL STALL"

I've put us into a steep climb and our speed has decayed to almost nothing. I pitch the nose down and increase the power to recover but I've overdone it. The instructor points out the over-speed warning, ignoring the director who is telling him that he's not supposed to be helping me.

The instructor started the flight with just 100 kilos of fuel so I barely have time to get the plane back under some semblance of control when I run out. "We're out of fuel," I say with a gasp.

"The weather isn't bad enough," complains the director.

"We're beneath the cloud," I explain. "Last time I flew straight through it."

"Can you add some lightning?"

"You want special effects?" The instructor taps at the iPad.

The camera man chimes in. "This is taking too long," he says. "Can't you crash it faster?"

"Yes, I can," I snap. I pitch down, hard, directly at the ocean. The flight instructor lurches for the controls as we race towards the waves but it's too late. The screen goes black.

The camera man leans forward, pushing the camera into my face. "We're dead," I tell him. This was more Germanwings 9525 than Flight 19 but at least it's the right plane for it.

"You are looking the camera."

"OK, that's good enough," says the director. "We need to get going, or else we won't have enough light at the museum.

I've been here over four hours and apparently we aren't done yet.

The flight centre supervisor comes back into the cockpit and motions the instructor to stay put. He grins at me. "Do you want to land it properly?"

Would I? "Oh yes, please!"

The director ignores him. “Everyone out, let's go!”

“I’m setting it up so she can land this time," says the supervisor.

"No, we need her. We're late."

The flight centre supervisor crosses his arms across his chest. “You can’t put her through all that and not allow her to land it even once,” he says, his voice a challenge.

The director glares at him and then takes a deep breath and agrees. “We need some time to get packed up anyway.” He leaves the simulator.

The supervisor kneels between me and the instructor, grinning. "Check this out." He takes the iPad. "We can set this up with historical data. When did this flight happen?”

"5th of December, 1945."

He keys it in. The landscape out the window shifts as the tall buildings disappear, replaced with fields and a stumpy looking white tower just three stories high. The runway is narrower and much shorter. This time my gasp is real.

We are in Fort Lauderdale in 1945.

"What time? I think I can recreate the real weather conditions and everything!"

I can’t believe they didn’t tell the director that this was possible. He would have loved this. But I don’t have time for guilt; the two men are already setting the plane up for me at 2,000 feet on final approach to the airfield.

I'm tired and it's all a bit much and I can't see the runway. I'm also grinning like a loon.

"You are descending too fast," say both of the men in the same breath and I realise we are only a few hundred feet above the ramshackle houses and the airfield is still over a kilometre away.

"I can see the runway," I say with relief.

The supervisor laughs. "You can see it because you are way too low."

Oh, right. I'm trying to fly the A320 like it was a Cessna 172 instead of using the navigational help of the glass cockpit. The director would be proud. Speaking of which, I think I can hear him pacing.

The instructor increases the thrust and takes over our power setting, getting us over the threshold. There's no time for a second chance. I use my last bit of mental energy to flare gently and then touch down onto the runway. It's almost a perfect landing.

I apply the brakes and lean back.

"Well done, Captain. Did you enjoy that?"

"Yes." I'm laughing with relief. "Thank you, that was fantastic." I turn to the instructor as I clamber out. "And thank you for saving our lives. Repeatedly."

Three minutes later, I'm bundled into the van and we're on the road again.

"You're doing great," says the director before disappearing into a dozen phone calls.

There's a new message on my phone as well. "How did the interview go?"

"I have successfully crashed an Airbus," I tap back. "Seven times. Six of them on purpose."

"What's that got to do with Flight 19?"

Not a lot. But I like to think that those boys learning to fly at Fort Lauderdale would have been impressed.

PS: I did not break the no-photography rule. All Airbus simulator images are taken from the flight centre's marketing material.

PPS: If for some reason you would like to see the German-dubbed television show about the Bermuda Triangle featuring someone called Sylvia Riley attempting to recreate a historic flight in a simulator, you can watch it online here. Just …don’t tell anyone I sent you.